Mapping the Future: Using Research to Better Understand Women's Health

Alicia Smith, PhD looks for discovery, breakthroughs for women

Alicia Smith, PhD is a self-professed "genetics geek."

That passion, interest and drive has spurred her to create a genetics lab at Emory that is making breakthrough discoveries that will help health care providers better identify and understand a woman’s risk for pregnancy complications and other health issues.

“Our projects are very translatable,” says Dr. Smith. “When we discover something, we can and do look for direct relevance to human health, which helps us understand how our genetic factors and environment work together to create risk. Then, we can optimize patient care.”

At the heart of the lab’s success is collaboration: She works closely with her dedicated team and health care providers across Emory and researchers around the world.

“Research is orientated to team science. When a number of different perspectives come together to address a research question, it’s far more productive than working in isolation.”

"Research is orientated to team science. When a number of different perspectives come together to address a research question, it's far more productive than working in isolation."

Alicia Smith, PhD

Dr. Smith sat down and shared additional insight on the work her lab is doing, and exciting opportunities to advance women’s health.

Q: What is your lab’s mission?

We are most interested in identifying modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for pregnancy complications and disorders that affect women, such as preterm labor, endocrine disrupting compounds and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

We look at epigenetics, which is a biological signature of how your body responds to your environment and, thus, can be modified. Non-modifiable factors include an individual’s inherent genetic code, which can’t be changed. However, if we find people with a predisposition for preterm birth, we can use that marker for screenings or drug targets to help manage that risk.

We are interested in genes that increase risk of preterm birth and other conditions. Finding those genes may tell us more about those conditions, and how we screen and, ultimately, treat them either by changing environmental factors or through medicines.

Q: How does your lab’s mission guide and/or shape the research being done?

Our research portfolio is rather diverse. The common feature is the role of estrogen and similar hormones to affect the way genes are expressed, whether that’s with PTSD, preterm labor, pregnancy complications or another women’s health issue.

Our focus has evolved over the years. A few of our early studies focused on cortisol and stress hormones during pregnancy. Pregnancy stress is linked to complications, such as preterm birth and low birth weight. We also looked at how stress relates to affected infants - from infancy to early child development.

Over time, we’ve gradually grown to recognize the importance of things other than cortisol in preterm birth. We’ve expanded our focus to look at a number of other risk factors as well.

Q: Which of your research projects are you most excited to share?

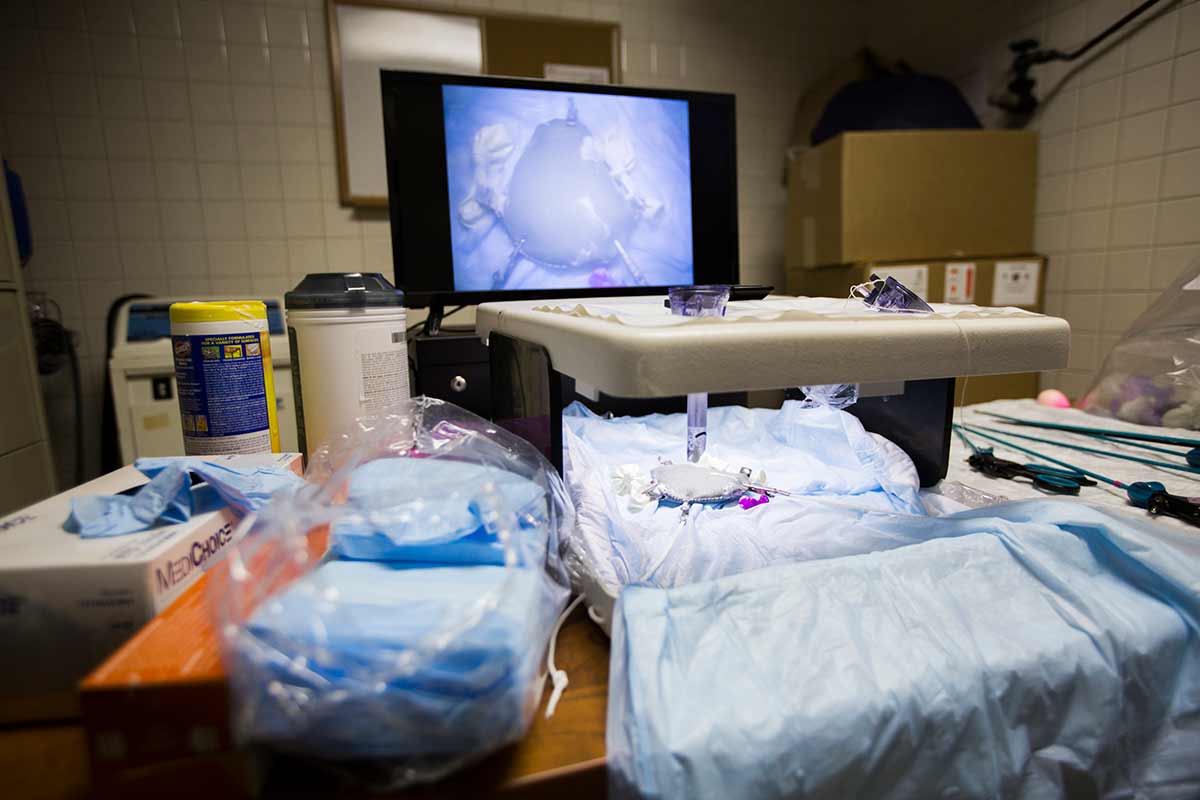

One of the things we’ve been particularly excited about is we identified a gene that could be used for early screening of a common delivery complication - fetal intolerance of labor, or fetal distress. It’s a common condition that women experience during labor and often have to go for an emergency cesarean section, which has a reasonable degree of risk associated with it.

We’ve found a gene whose epigenetic pattern is highly predicative of fetal intolerance of labor, and we can measure it in the late second semester or early trimester - months before women deliver.

When we can screen women later in the pregnancy and identify who is most likely to have an emergency C-section, then she and her health care team can prepare for that likelihood. This is particularly important for women planning home births and rural deliveries where access to health care is limited.

These findings are exciting for a number of reasons, including the potential to help reduce infant mortality, which, unfortunately, is a problem in Georgia.

Q: What are some other promising studies, and what impact might they have on better understanding women’s health?

One of our graduate students is doing a really amazing job of identifying intergenerational transmission of health risk. She’s working with Dr. Michelle Marcus in Epidemiology. They are showing that there are different mechanisms that could be responsible for the fact that people who have been exposed to endocrine disruptors have children that experience fertility problems - even though those children did not have direct exposure to the disruptor. They are trying to identify how endocrine disruptor exposure changes genes even in the second generation.

Endocrine disruptors are a wide class of compounds that mimic hormones in the body. For this study, we are working with another research group that is focused on a brominated flame retardant that was introduced into the food supply of a Michigan town in the 1970s. While this particular compound is no longer made in the U.S., what we learn from this study can teach us about the effects of compounds that are still made.

Senior Research Specialist, Dawayland Cobb, MS is performing a picogreen assay to quantify the amount of DNA found in each sample. The goal is standardization to ensure that all samples used contain the same amount of DNA for testing.

Another interesting research study is EmPOWR, which is an initiative we are doing on behalf of the Gyn/Ob Research Division. We are working to build a clinical registry and repository to help better answer questions related to women’s health.

I’m excited about this project because these are the sorts of large initiatives that are really important to push scientific research and healthcare forward. Many studies tend to be very small and have a number of limitations. By building this registry and depository, we are hoping to leverage our clinical encounters and research potential in a way that doesn’t inconvenience our patients.

When participants sign up, we will be able to collect biological samples, such as blood, during regularly scheduled appointments. Participation wouldn’t require any additional visits or anything outside of what she would have to do for care. This will allow our department to collectively have the ability to do larger women’s health studies.

Q: What are other exciting advances your lab is working on?

We have a lot of interesting and exciting studies. But one thing that is very important is that we train people in research, and that trains people how to think objectively and critically. That type of training is inherently invaluable whether a research project works out or not. Having critical thinking skills is so important for clinicians, scientists, and really, anyone.

Learn more

Read more about Alicia Smith, PhD’s lab and research projects.